Census records are one of the most important types of genealogical records, containing a wealth of information you may not find in vital records and allowing you to track your ancestors’ progress over time. While most genealogists focus on the major content in a census record (birthplace, age, relationships), a more thorough process can help you extract much more and expand your genealogy research.

Why Census Records Are Important in Genealogical Research

For many genealogists searching for their U.S. ancestors, a census record is typically the first type of record to appear in a basic search on MyHeritage. Depending upon the type of census record and the census date, you can locate information that places an ancestor in a specific location on a specific date as well as others in that ancestor’s household.

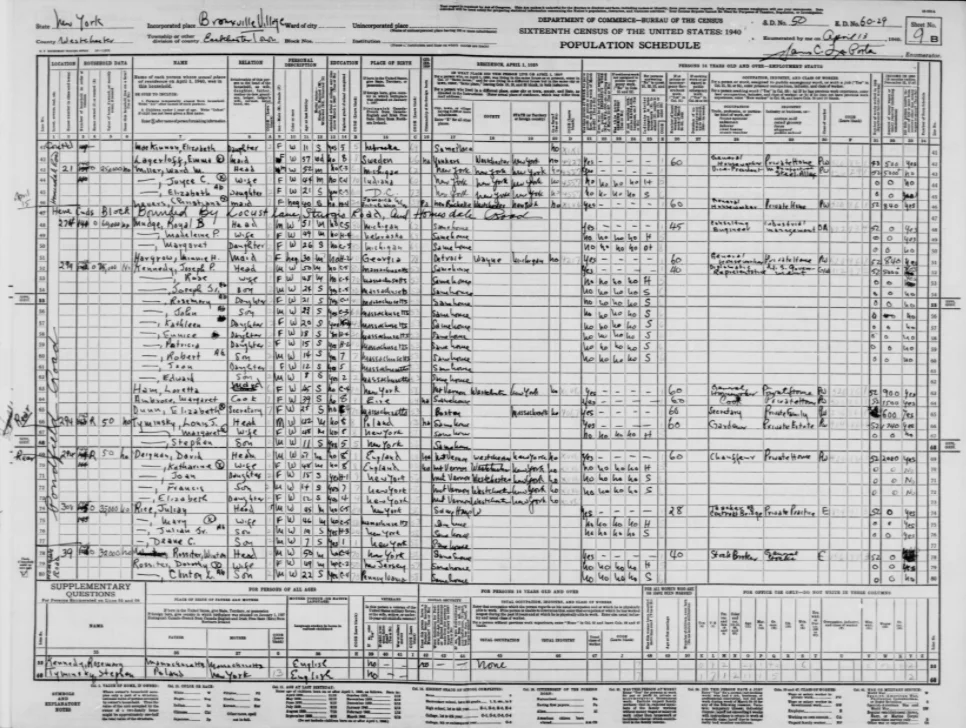

- U.S. Decennial Census: Per Article 3 of the United States Constitution, a “headcount” of “residents” is to be taken every 10 years. The Population Schedule is the most useful of all the decennial census schedules. And since the first census conducted in 1790, the information gathered has expanded to include education, employment, and more.

- U.S. Census Schedules: Depending upon the specific decennial census, you may find specialized schedules such as Agriculture, Business, Mortality, and others. Usually the entries are referenced to in the Population Schedule.

- Territorial and State Census: Some of the states conducted their own censuses, often “on the fives” — meaning a year ending in 5 in between each decennial census. Territorial censuses were often conducted before a state was admitted to the Union, especially as a means of determining if the territory met the minimum population requirement.

Understand the History and Background of Each Census and Its Respective Records

Not all censuses are the same, especially United States censuses. Each decennial census had its own sets of questions, enumerator instructions, and even method of carrying out the enumeration process.

Don’t assume that, for example, the 1950 U.S. Census is the same as the 1940 U.S. Census. Here are some resources to understand each census:

- FamilySearch Wiki: Similar to Wikipedia, with a collection of close to 100,000 articles related to all aspects of genealogical research.

- United States Census Bureau: The Census Bureau has a vibrant History section covering all aspects of the US Census. Each decennial census has an overview, index of questions, census forms, enumerator instructions and more.

- IPUMS USA: The “Integrated Public Use Microdata Series” contains resources related to 16 of the decennial censuses through 2010 including the American Community Survey.

Consider creating a “census research toolbox” as a place to save links to specific resources. A great format is a Census Research folder in your internet browser Favorites or Bookmarks.

Search Tips for Locating Census Records

While census records are often the first type of record located when doing a general search on a genealogy platform like MyHeritage, you may need to be flexible with your search methodologies if you just can’t find that record.

- Search broad, then go narrow. Very often genealogists try to use a very narrow search to locate census records. Sometimes too much information causes you to overlook the record you want. Start with name, location, and a birth date. Then use the edit search or filter feature to narrow down the search results.

- Don’t use exact names. Be flexible! Many genealogy sites like MyHeritage will allow you to search for given name and surname variations. Remember that often the enumerator wrote down how a name sounded, especially for immigrant families. See Guessing a Name Variation at the FamilySearch Research Wiki.

- Use the card or collection catalog. Narrow search results to a specific census is to first review the list of census databases via the site’s list of databases. Then select the database and search within only that record set.

- Browse the record images. A searchable index to a census record set may contain errors. As a last resort, identify the enumeration district where your ancestor should be listed, and browse through the set of images.

Access, Download, Cite, Rename, and Preserve

When you locate a census record that you want to use in your research, the following steps should be taken:

- Access: For most genealogy record sites like MyHeritage, there is a record and an image for each search result. The record contains a transcript of the information, a source citation, a link to the specific record database, a list of related or suggested records, and a link to the record image.

- Download: Save the census record image to your computer or your cloud file program. Always save record images right away, since some record databases have limited licenses with the genealogy platform. In addition, always save a copy outside of the genealogy platform so that you have an easily accessible copy.

- Cite: Crafting a source citation sounds difficult, but it really isn’t. Think of yourself as a genealogy journalist reporting on the census record. This means stating the “Who, What, Where, When, and Why” much like a news reporter would do. For example: “1940 United States Federal Census, New York, New York, New York, Population Schedule for AUSTIN Alfred, MyHeritage [online database] (https://www.myheritage.com/research/record-10053-147600973/alfred-j-austin-in-1940-united-states-federal-census) accessed 24 Jan 2022.” An alternative would be to use the “Cite this record” function available on the MyHeritage record page and copy the citation information.

- Rename: Once you have downloaded the census record image, rename the file using your preferred naming convention. The goal: you should know what is in that file without having to open it. For our example I use AUSTIN Alfred b1916 1940 US Federal Census Pop Sched 19400401.

- Preserve: Make sure you are using the 3-2-1 Backup Method to preserve your work and ensure future access. This means:

- 3 different backup copies

- 2 different storage media

- 1 cloud storage platform

A good example would be creating 3 copies of the file and storing them in 3 different locations; then making sure at least two of the copies are on different storage media such as one on a USB flash drive and the other on a portable solid state drive; and finally upload one copy to a site like Dropbox or Google Drive.

These steps are a good strategy for any genealogy record you locate online. And execute these steps right away! Don’t tell yourself, “Oh, I’ll do the source citation later” or “I will rename that file later.” Do it now and you’ll easily locate what you need related to that record in the future.

Extracting Census Information

When working with a census record, your goal should be to extract as much information as possible. One method is to use a tracking system such as the Genealogy Research Log; or you could create a “census abstract” which uses a fillable blank population schedule for a specific decennial census.

Many genealogists prefer the abstract method since it is easy to isolate the information for a specific person or family. FamilySearch has a series of fillable forms (requires the free version of Adobe Acrobat) which you can find here.

Look for the “Not So Obvious”

Another reason why I use a To-Do List and a genealogy research log is to track every bit of information found on a census record and to formulate theories about new information and where those clues might lead to new records.

- Street Name: Did the street name change over time? Does the street exist today? (Use Google Maps and Street View.)

- Dwelling Number: If the family lived in an apartment building, often there will be one dwelling number with multiple family numbers. For immigrant families, review the entire set of families in the building and see who spoke the same language, was born in the same country, etc. This is valuable F.A.N. Club information (“Friends, Associates, and Neighbors”) for cluster research.

- House Information: Did your ancestor own their home, and if so, what was the value? Or did they rent an apartment, and what was the monthly rent? This information is a good indicator of their economic status at the time.

- Relationship to Head of Household: For certain censuses, the enumerator was limited in the ways to describe a relationship. So a “cousin-in-law” might be listed as a “boarder” or “roomer” or “lodger.”

- Marital Status: Often a woman separated from her husband would be listed as a “widow” rather than “divorced,” which brought a negative reputation in some small towns. Search for the husband, and you may find him living a few towns over or even in a nearby county with another woman and family.

- Education: Prior to the mid-20th century, many people only completed the 8th grade of school and then went to work to support the family. For those completing high school, look for university records.

- Occupation: Trace an ancestor’s occupation over time and also see who else on the page had the same occupation. There may be a F.A.N. Club clue which can help break down a research brick wall.

- Miscellaneous Information: Each census asked specific questions such as “Do you own a radio” in the 1930 US Census. Review the list of questions for each census and see what insights the responses might bring.

Additional resources:

- 10 Tips for Successful U.S. Census Research — handout by Thomas MacEntee from GenealogyBargains.com

- Clues in Census Records, 1850-1930 — National Archives

- Genealogy Research Log – Excel — template by Thomas MacEntee from GenealogyBargains.com

- United States Census Bureau – History

Learn more

This article was originally written as a handout summary of a Facebook Live session with Thomas MacEntee, which you can view in its entirety here. It is also available as a downloadable resource here.

For more information on Thomas and his FREE genealogy resources, visit https://genealogybargains.com/thomas-macentee/

For more resources on researching the U.S. census on MyHeritage, see:

- How to Search U.S. Census Records on MyHeritage — how-to video

- MyHeritage’s U.S. Census Hub — a minisite dedicated to researching U.S. census records

- Using MyHeritage to Prepare to Rock the 1950 U.S. Census — Facebook Live session with Lisa Louise Cook