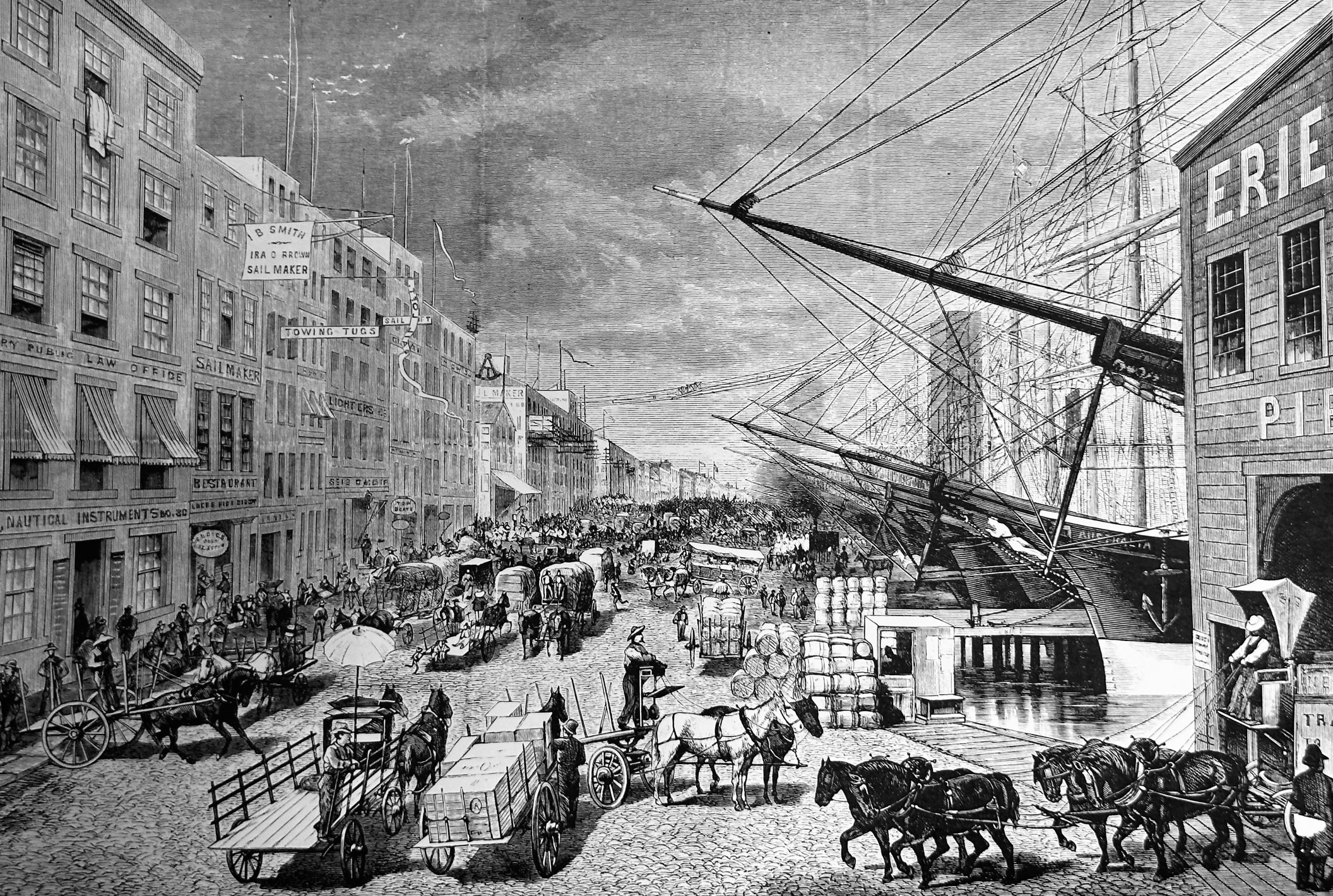

New York City as a port is unrivaled in the Americas as a destination of immigrants coming to North America. Well over 70% of all immigrants to the U.S. from the 1850s to the end of the 19th century transited through the port of New York. No fewer than 12 million future Americans passed through the doors of Ellis Island from its establishment in 1892, until its closure in 1954.

Many of the immigrants who arrived in New York City stayed and built new lives there, but many moved on to other destinations throughout the country. If you have an immigrant ancestor who arrived between 1820 and 1957, no matter where they settled later on, there’s a good chance you will find them among the passenger lists of New York.

Search Ellis Island Records and Other New York Passenger Lists, 1820-1957

In this article, we’ll touch on the history of these important records and explore what you can learn from them about your immigrant ancestors.

A brief history of passenger lists in New York

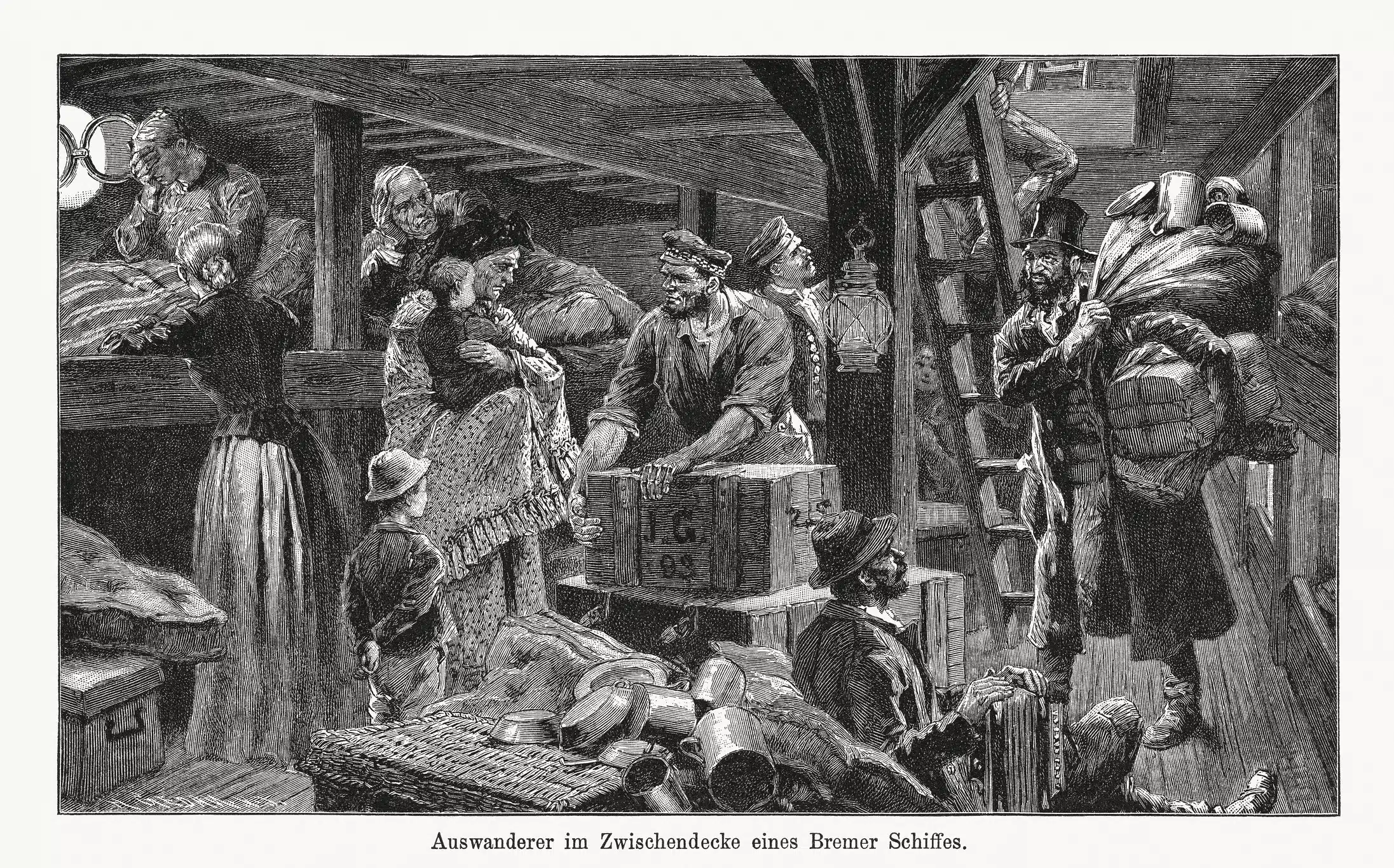

People began immigrating to America well before the 19th century, but we have very few immigration records before 1818. In December of that year, Representative Thomas Newton of Virginia proposed a bill to regulate and reform passenger ships entering ports from abroad. This was primarily due to very dangerous overcrowding conditions that were occurring on these ships. Of approximately 5,000 passengers who sailed from Antwerp, Belgium, for the United States in the previous year, no fewer than 1,000 had died before reaching their destination port. On one ship sailing from a European port, more than 700 of the 1,267 people aboard died in transit — well over 50%. Congress acted quickly to respond to the situation, and on March 2, 1819, it enacted legislation and brought about the Steerage Act of 1819, also called the Act to Regulate Passenger Ships and Vessels.

Steerage refers to the lowest, least expensive class of accommodation that these ships offered or that they sold tickets for. The vast majority of people on these ships were in steerage class — well over 80 or 90%. Under this new act, masters or captains of vessels arriving at American ports from abroad were required to submit a list or a manifest of all passengers to the collector of customs in the port where the ship arrived. All known custom passenger lists have been accessioned by the National Archives, and the customs passenger list for the Port of New York did survive fairly well going back to 1820.

Over the next 60 years, Congress passed additional legislation several times to fill in loopholes in the 1819 law, but it became apparent that a more serious reform was required. That led to the passing of the Immigration Act of 1882, which provided greater provisions against overcrowding, including:

- Requirement to have an on-board hospital with a doctor equipped with medicines and supplies

- Requirement to provide 3 cooked meals per day for passengers

- Size requirements for sleeping quarters, which had to be at least two feet wide and 6 feet long

Immigrating to New York

In 1845, a steerage class ticket from Liverpool to New York cost about 3 to 5 pounds. The voyage generally took 3-6 weeks, and these packet ships, as they were called, would carry between 200 and 300 passengers.

By the 1910s and 1920s, ships had evolved quite a bit and were able to make the trip much faster, typically about 6 to 10 days. These ships could carry several thousand people, including hundreds of crew members.

Prior to 1855, custom agents met ships at the various piers in the city to collect passenger lists. There was no official immigration station, and information was collected wherever the ship was assigned to dock.

In 1855, an immigration station was established at Castle Garden in Lower Manhattan, and it functioned until 1890, when the station was moved to the Barge Office on the eastern side of Lower Manhattan. During the period between 1820 to 1891, just over 11 million immigrants arrived in the port of New York. That’s equivalent to twice the current population of Norway!

Ellis Island opened its doors on January 2, 1892. The first immigrant to enter the immigration building at Ellis Island was Annie Moore, a 15-year-old girl from County Cork, Ireland, and she was presented with a $10 gold piece to commemorate her role in U.S. history. 12 million immigrants were processed at Ellis Island from that day until 1954 — with a brief pause between 1897 and 1900, when a fire destroyed the building and the immigration station was temporarily moved back to the Barge Office while it was rebuilt.

Waves of immigration were influenced by world events including famines, wars, and economic drivers such as depressions, “panics,” and the Homestead Act of 1862. World War I caused a massive drop-off in immigration in 1914, but it picked up again due to the Depression of 1921. In 1924, the Immigration Act was passed, and that made it much more difficult to immigrate. Immigration numbers dropped sharply as a result.

Researching New York passenger arrival records on MyHeritage

The National Archives microfilmed passenger lists and published them in two sets: Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, 1820-1897, and Passenger and Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New Work, 1897-1957. At MyHeritage these sets are combined into one collection: Ellis Island and Other New York Passenger Lists, 1820-1957.

In 1898, a question was added to the form inquiring as to whether the migrant is planning to join a relative and if so, to list their name and address. In 1907, another question was added requesting the name and complete address of a relative or friend in the country where the person came from. The MyHeritage index includes the secondary individuals in both of these columns, adding 28 million names and relationships to our New York passenger database.

It’s important to note that these records are double-sided. The second page often gets missed. At MyHeritage, we stitched the two images together into one so you can easily read the entire record without missing any information.

Sample Ellis Island passenger list record

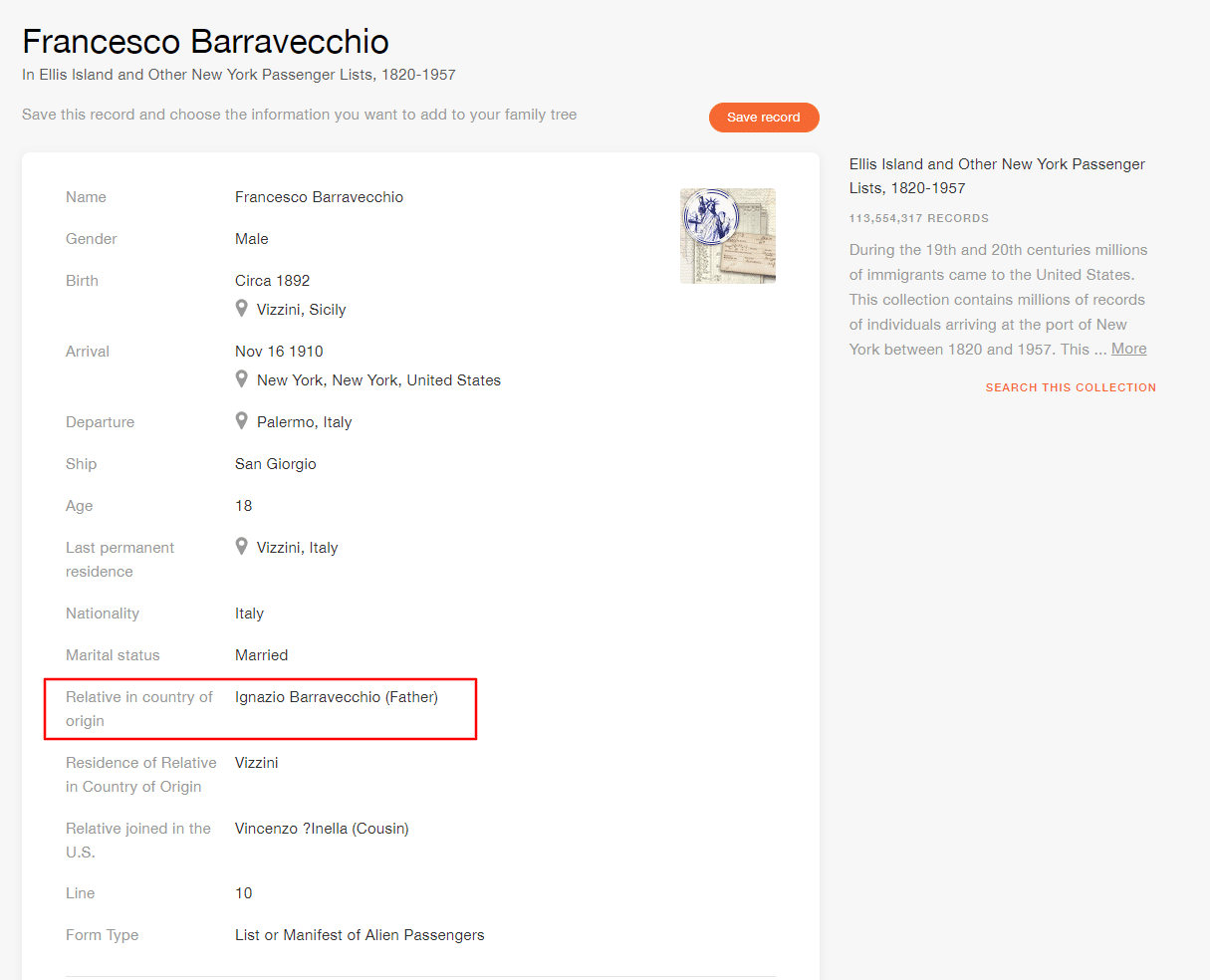

Let’s take a look at the example of an Italian gentleman, Ignazio Barravecchio, who appears in our index 4 times.

The first record of Ignazio in the collection is this one from 1910. This is actually a record of Ignazio’s son, Francesco, but because Francesco mentioned his father as a relative in his country of origin — in this case, Vizzini, Italy — Ignazio appears in the index.

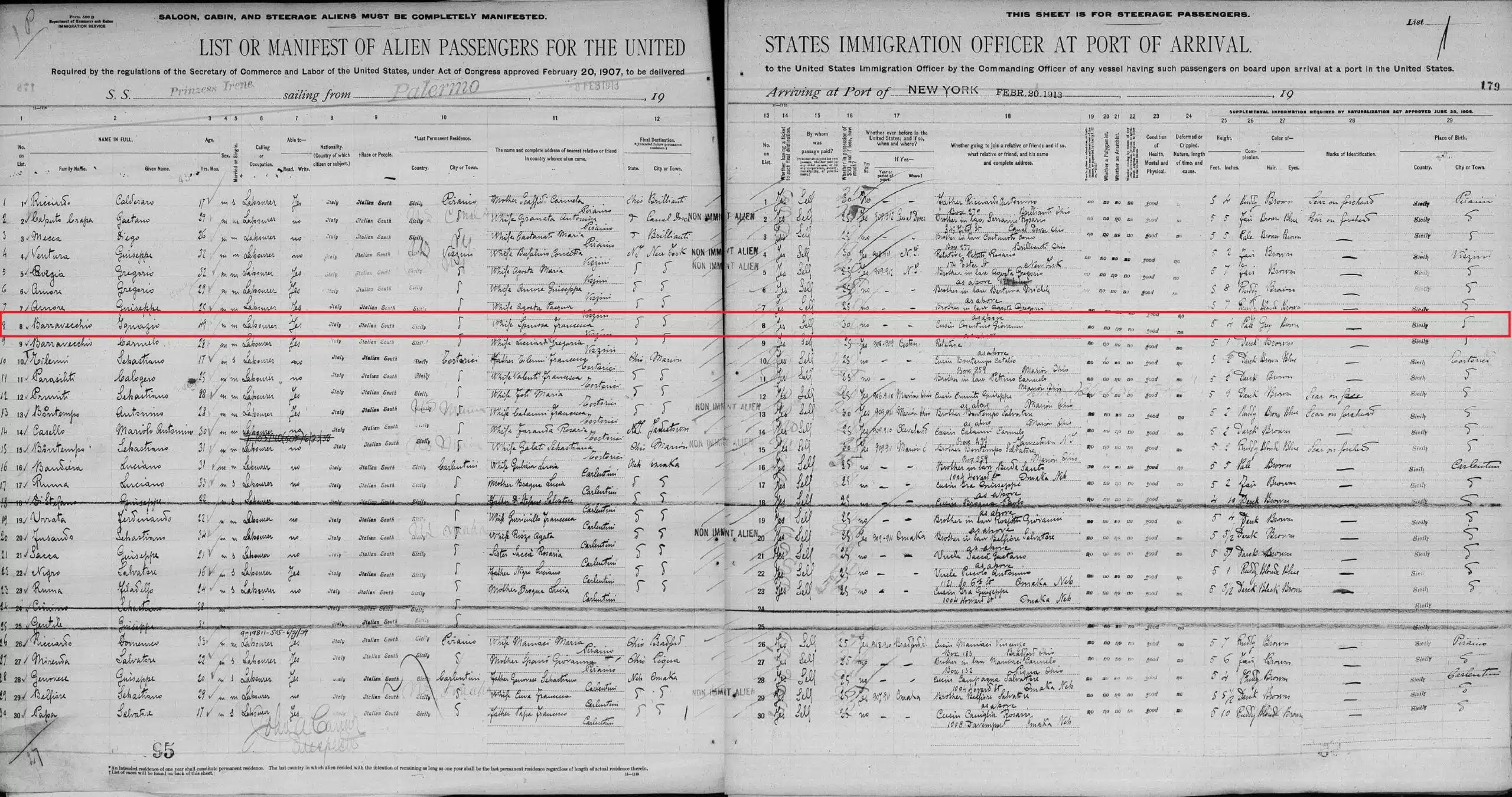

The second record is of Ignazio’s own arrival in 1913:

The record includes the name of a cousin he’s joining in the U.S., Giovanni Cosentino. It lists his address as “as above,” and we see that there’s a group of people living in the same residence expecting 6 passengers from Vizzini who are arriving on this ship, including another Barravecchio who appears right after Ignazio on the list.

Looking at the original scan of Ignazio’s record, just from that one line, we learn the following:

- His age: 49

- His marital status: married

- His occupation: laborer

- His literacy: he can read and write

- His nationality: Italian

- His ethnicity: South Italian

- His country of origin: Sicily

- His city of origin: Vizzini

- His wife’s full name: Francesca Spinosa

- His final destination: New York

- He funded his own travel

- He has $30 with him (worth about $950 in today’s U.S. dollars)

- He has never been in the U.S. before

- He is in good physical condition

- His height: 5’4″

- His complexion: pale

- His eye color: brown

- His birthplace: Vizzini, Sicily

It’s an incredible wealth of information about this individual. The fact that the pages are stitched together allows us to easily locate additional information about him on the second page.

The following two records are for relatives who arrived later: his cousin Pasquale Depetro and his son Vito, who both indicated him as a relative located in the United States.

Additional resources for researching U.S. immigrant ancestors

Below are some additional passenger lists and records of American immigration available on MyHeritage:

- New York Castle Garden Immigrants

- New York, Passenger List Book Indexes 1906-1942

- Passenger and Immigration Lists, 1500-1900

- All U.S. immigration & travel record collections on MyHeritage

Learn more about researching U.S. immigrant ancestors on the MyHeritage wiki:

- Ellis Island Immigration Records

- Castle Garden Immigration Records

- Immigration to the U.S.

- U.S. ports of entry for immigration

Search the Ellis Island and Other New York Passenger Lists, 1820-1957 collection

This article was adapted from part of a webinar given by Mike Mansfield on Legacy Family Tree Webinars on April 12, 2024. Watch the full webinar for free: Searching for Your Family in NYC? Resources and Techniques at MyHeritage and Beyond