Reading old handwriting can be a major challenge for researchers. Perhaps you’re familiar with this scenario: you’ve finally located an exciting handwritten historical document that just might contain the information you’ve been searching for. You sit down to read it and… hieroglyphics. You can’t make out a word.

Search historical records on MyHeritage

It could be an old script using letters that were drawn differently than they are today. The ink could be faded or smudged. The writer may have been in a hurry… or could simply have had terrible handwriting! And that’s without mentioning the added difficulty of transcribing a document in a language you don’t speak.

The good news is, the human brain is wired to recognize patterns. You may be surprised to find that you can successfully transcribe a lot more of those apparently inscrutable scribbles than you think. There’s a whole field of study dedicated to historical handwriting and writing systems: paleography. The techniques used by paleographers and historians can help you decipher your document, no matter how old it is.

In this article, we’ll explore some of the strategies I learned as a citizen scholar participating in the Deciphering Secrets project. Created by Roger Martínez-Dávila, Ph.D., Professor of History at the University of Colorado, Deciphering Secrets has trained tens of thousands of students to create original transcriptions of manuscripts from Spanish archives through a series of free online courses. You can learn more about the project and find links to each of the 3 courses here.

Learn about writing styles from the period

While most of the common writing systems have remained largely unchanged for hundreds of years, technological and cultural developments can influence the way people write.

Just 30 or 40 years ago, cursive script was a completely standard form of handwriting in the United States and was required for use in academic settings. Today, cursive is no longer even taught in schools, and many young people can no longer read it.

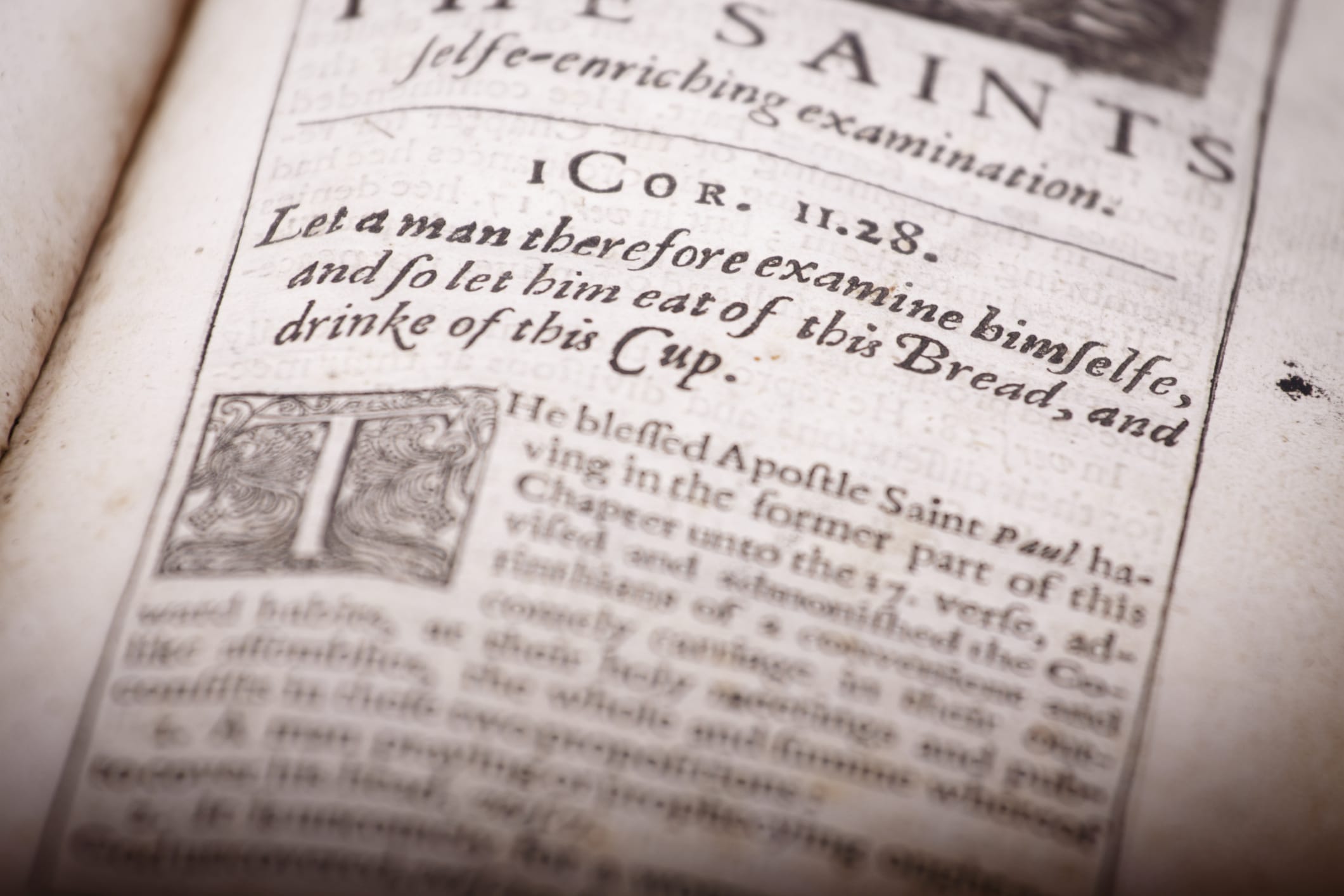

In Elizabethan-era English, the letters “i” and “j” were used interchangeably, as were the letters “u” and “v.” Another letter called the “thorn” (þ), no longer used in modern writing, represented the “th” sound. The “long s” — an “s” written like an “f” without a line across it — was used in printing even into the nineteenth century, as you can see in the page from a 17th-century Christian text below:

The words “himself,” “so,” “Blessed,” “apostle,” “verse,” etc. contain the “long s” that could easily be confused with an “f” by a modern reader.

Knowing the characteristics of the writing system in the era in which your document was written can save you a lot of head-scratching.

Beware of abbreviations and spelling variations

Throughout most of history, ink and space on the page were precious resources. Scribes often used abbreviations to indicate common words, phrases, and even names — not unlike the acronyms and symbols used in text messages today. Some indications that what you are looking at might be an abbreviation include:

- A tilde (~) over a word

- A symbol that doesn’t quite look like a letter

- A few letters written above the rest of the word

Search for a list of common abbreviations from the period. Even if you can’t find one, it can help a great deal to keep in mind that some words on the page may not be full words at all.

It’s also important to remember that words may not be spelled the way you are used to, especially if the document is very old. Spelling only became standard in relatively recent history. The same word may be spelled several different ways, even in the same document.

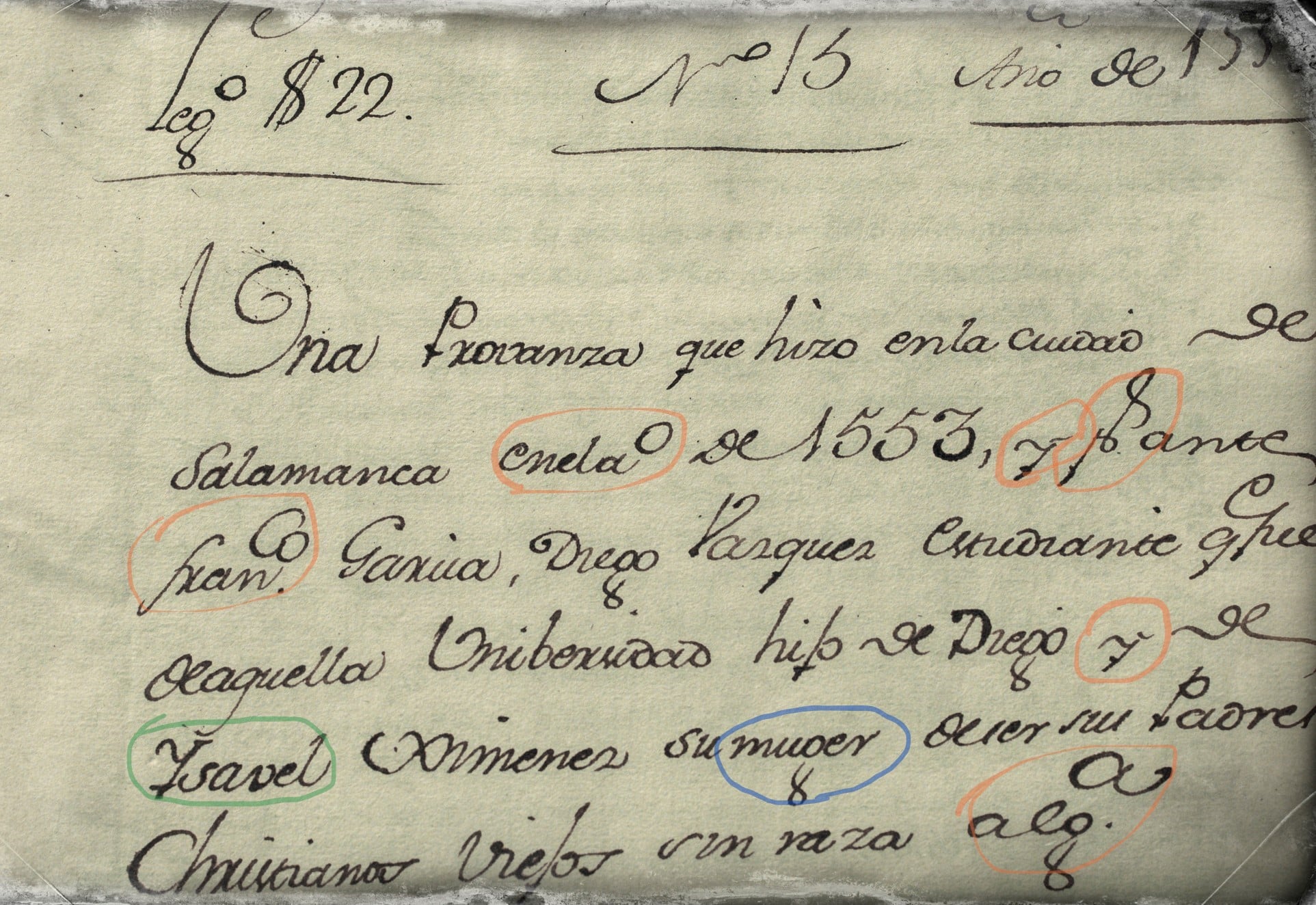

See for example the document below, which was written in Salamanca, Spain, in 1553:

The words circled in orange are abbreviations. The first one, for example, says “enela” with an “o” written above. It stands for “en el año,” meaning “in the year.” The one at the beginning of the line below says “Fran” with “co” above; it likely stands for Francisco, a common Spanish given name.

The name Isabel, circled in green, is spelled Ysavel: the letters “y” and “i” and the letters “b” and “v” were often interchanged in old Castilian writing. The letters “j” and “g” were also often interchanged, as we can see from the spelling of the word “mujer” (meaning “woman” or “wife”) as “muger” (circled in blue).

Give your brain a chance to get used to the writing

When you first approach the document, Dr. Martínez-Dávila recommends simply scanning the whole thing with your eyes without trying to transcribe anything.

As mentioned above, our brains are wired to seek out and find patterns. The more you familiarize yourself with the symbols on the page, the more your brain will begin to make sense of them. You may walk away for a few minutes, then come back to to the page and find that some of those incomprehensible scribbles are suddenly registering as complete words. In fact, if you get stuck, setting the document aside for a few days and coming back to it with fresh eyes can work wonders.

Digitize your document

If the document isn’t digitized yet, I highly recommend doing so using a high-quality scanner. Creating a high-quality scan will allow you to zoom in on the image and enlarge the text, enabling you to pick up on markings or nuances you might not have seen otherwise. In addition, working with a digital version or a printed copy rather than the original both protects the original from damage and allows you to mark up the copy.

Start with letters, abbreviations, numbers, and words you recognize

Don’t try to transcribe the document in order. If any letters, abbreviations, numerals, or words jump out at you right away — mark them or write them down. If you’re working with a copy, highlight or circle words or letters you recognize as well as symbols that are likely to be abbreviations (even if you don’t know what they mean yet). Locating common words will help you understand how the letters are connected to each other. It may also show you how additional letters or numbers were written.

For example, in the Spanish document above, the “g” looks a little unusual. The squiggly line beneath it curves back on itself in the opposite direction of what I’d expect, and in some cases appears detached from the upper section of the letter. I might have guessed that it indicated an abbreviation, or was perhaps a “p” or a “q.” However, I know it’s a “g” because two of the words in which it appears are definitely the name Diego:

Context is everything

If you speak the language of the document, you will find it much easier to decipher, because you can leverage your knowledge to extrapolate missing letters and words from context.

Still, it’s not impossible to transcribe a document in another language. Dr. Martínez-Dávila recommends searching for cognates — words with similar meanings and spellings in both languages, such as “traditional”/”tradicional” in English/Spanish) — and leveraging these for context.

As you can see above, knowing common names used in that part of the world can also help provide important context.

Learning some basic vocabulary can help, too, such as:

- Common connecting words, like “of,” “to,” “on,” “the,” etc.

- Pronouns (e.g. I/you/he/she/they) and possessive pronouns (e.g. my/your/his/her/their)

- Family relationships: father, mother, son, daughter, wife, husband, etc.

- Words relating to time, such as “year,” “month,” “date,” days of the week, etc.

- Other words that might be related to the document, such as inheritance, property acquisition, or lifecycle events

Think flexibly

If you think you understand what some of the letters are or have a pretty good idea of what the word should be, but are still struggling to figure it out — try setting aside your initial assumptions and thinking outside the box.

Ask yourself: what else could this be?

Perhaps that letter you were sure was a “y” or a “g” is actually a capital “E”? Maybe the two words at the end of one line and the beginning of the next are actually one longer word that was hyphenated? What if you’ve been assuming that the word following the preposition “on” must be an object, when in fact it’s a concept or an idea?

Be creative, and new ideas might occur to you that will help you crack the code.

Leveraging MyHeritage features to help read old handwriting

The Photo Enhancer may specialize in bringing blurry faces into focus, but did you know that it can also help clarify text? If some of the writing in the document you’re reviewing is smudged or faded, the Photo Enhancer might be able to sharpen it. Learn more about using the Photo Enhancer in the following article: Enhance Your Family Photos Using the MyHeritage Photo Enhancer

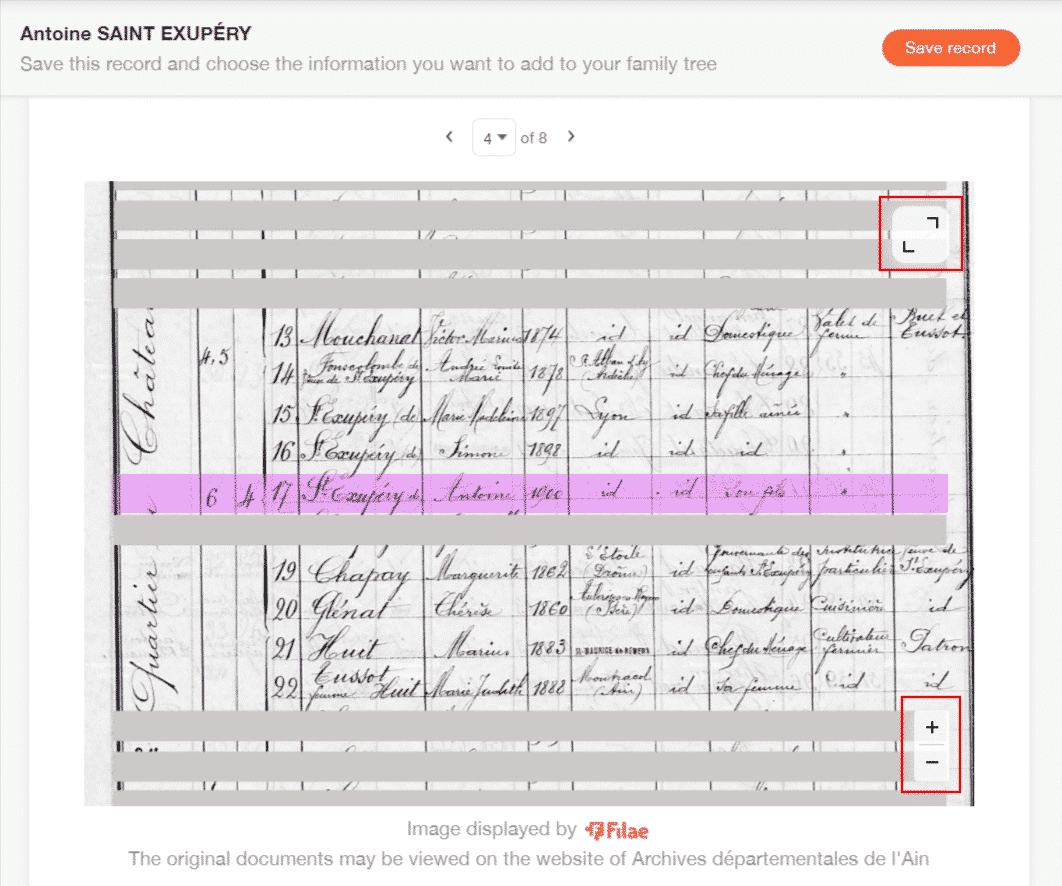

When viewing scans of handwritten historical records on MyHeritage, you can use the plus and minus buttons on the bottom right corner of the view window to zoom in and out. However, you may find it easier to work in the full screen mode. You can access it by clicking the full screen button on the upper right corner of the window.

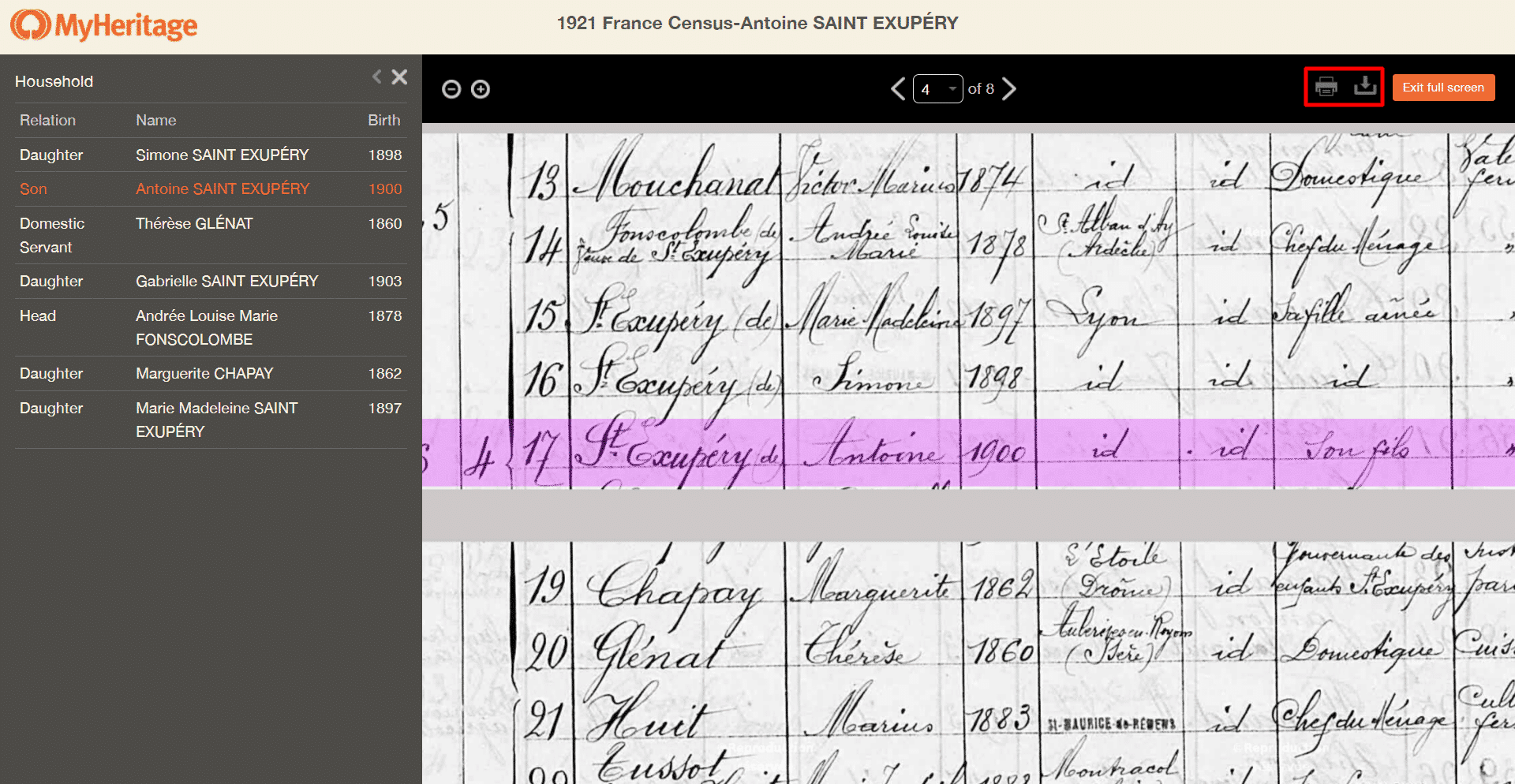

From the full screen mode, in addition to allowing you to zoom in and out, you can print or download the document by clicking the icons in the upper right corner. With some types of records, such as the census record shown here, the display also points you to the specific place on the page where the record you were viewing is located, and shows a list of all the members of the same household to give you more context.

Deciphering old handwriting may seem daunting at first, but if you think of it as a puzzle, you may find that it’s both fascinating and fulfilling. Stay patient, persistent, and curious as you uncover the valuable knowledge hidden within these documents. With the right mindset and tools, you’ll be well on your way to unlocking their secrets.