Every genealogist’s dream is to find their ancestors in the census. This type of resource is a fountain of information, including facts and historical details about a group of people — not only those living in the same house, but sometimes those living in the same area.

Unlike vital records — which may or may not exist for your ancestor, and may or may not be accessible — censuses are very easily accessed and often indexed for quick and easy searches. They follow family members over the decades of their lives, providing a glimpse into a family’s life while enabling you to place your ancestors in their historical context.

In this article, we’ll explore the background of the U.S. census and how it evolved, and provide some expert tips on tracing your family story using census records.

Why are censuses taken?

Governments take censuses for a wide variety of reasons. To name a few:

- To redraw voting districts

- To meet the needs of appropriate representation in legislatures

- To redistribute congressional seats

- To estimate federal spending among states

- To make decisions about education or transportation services

- For purposes of military recruitment

- For electoral votes

While genealogists benefit from these government records, we often forget that these records were never created for genealogical purposes. We might become frustrated with the questions that were asked — or not asked — and how long it might take us to gain access to this information.

About the U.S. census

Censuses are conducted in most countries once every decade. Mandated by the U.S. Constitution, the decennial census started in 1790. Some state census enumerations did occur on the 5-year mark, halfway between federal censuses. A special Native American federal census was taken between 1885 and 1940.

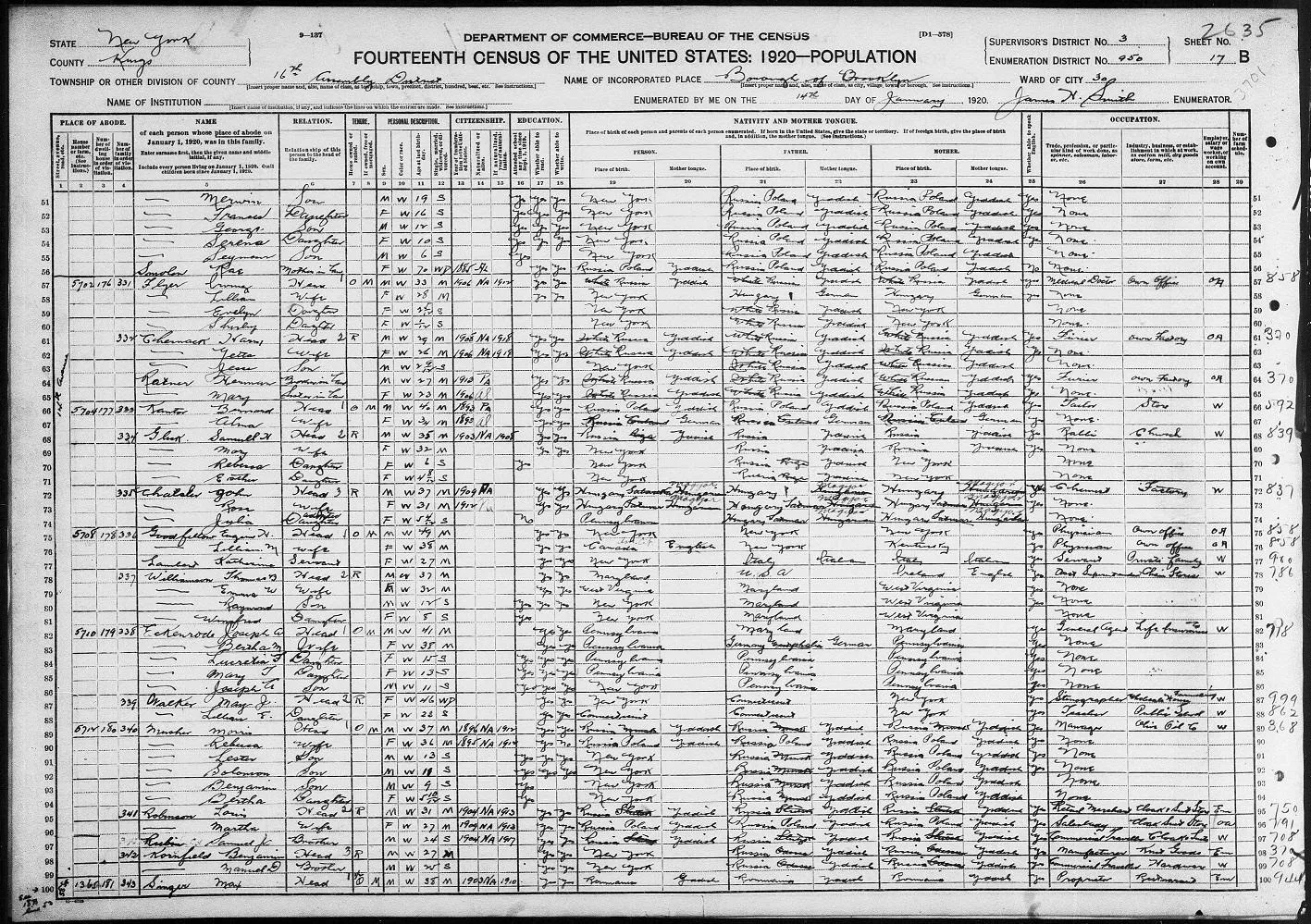

The publicly available census records were meticulously structured and filled out by hand, and they present only the facts — no photos or commentary. The questions and amount of information collected has grown and diminished over the decades. Census records contain details such as:

- Names of everyone in a household

- What language they spoke

- Whether they could read or write

- Whether they attended school that year

- Marriage information

- Age (only the 1900 Census included the month and year of birth, to the chagrin of many genealogists)

- Place and date of birth

- Immigration information

- Place of residence

- Family unit

Some censuses even asked for information on mortgages, or whether the family had a radio (as the 1930 census did).

How the U.S. census evolved over the decades

Beginning with the first federal census, only the head of household was listed by name. In 1840, the census gave the number of individuals living in the property along with their age, sex, and race. A second page listed the status of pensioners living in the household, including those from the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812.

Starting with the 1850 census, everyone in the household was listed, but was not until 1880 that the census also included the relationship of household members to the head of household and their parents’ birthplaces.

The 1900, 1910, 1920, and 1930 U.S. censuses recorded information about immigration and naturalization. Exact questions vary in each census: they provide the year of immigration, number of years in the U.S., naturalization status (alien, filed first papers, or naturalized), and year of naturalization. This data can help you search for the ship they came on and its passenger list as well as naturalization records. These, in turn, can help you identify the immigrant’s village of origin, nearest kin in that village, and sometimes their original surname.

Some researchers say the “radio” question in 1930 was asked to gather information on consumerism and marketing. Others think it was a way to understand how the government might be able to communicate with citizens. This census also asked if people owned or rented a home and how much it cost. In addition to their occupation, it asked if the person was employed. Remember — this was during the Depression, and the government needed to know which occupations had higher employment levels and to estimate unemployment rates.

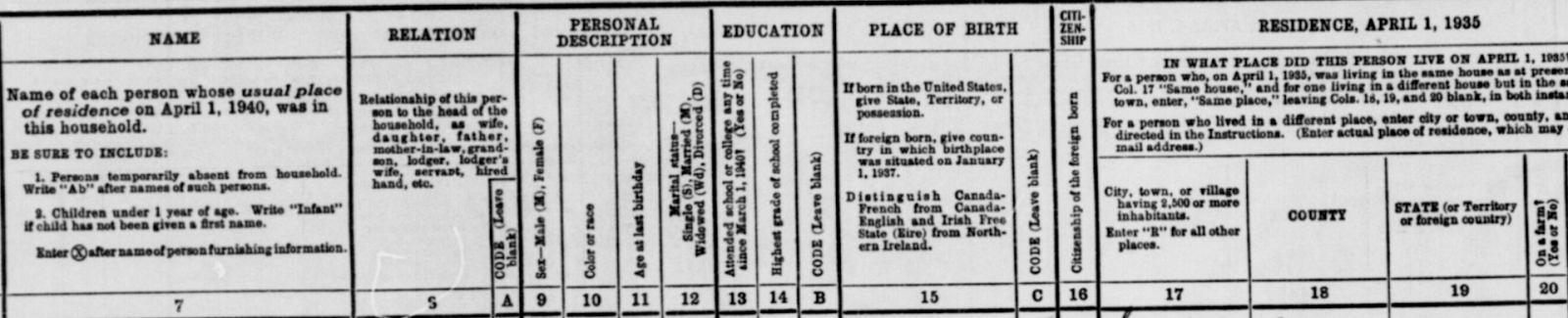

Column 14 of the 1940 U.S. Federal Census indicates the highest grade level the person completed. That census also tells you where the person resided in 1935 (columns 17–20), which is valuable if a state census is not available.

What happened to the 1890 census records?

In January 1921, a fire broke out in the building where the 1890 census records were being stored and destroyed almost all of them. That is why you are unlikely to find records of your family from 1890 in U.S. census record collections. One of the biggest advantages of the U.S. City Directories collection on MyHeritage is that it provides alternate coverage for this period.

When are census records released to the public?

In the U.S., there is an embargo on releasing census data until 72 years after it was collected. So if you want to research an ancestor who was born in 1950, you’ll need to wait until the next census is released to the public on April 1, 2022.

Expert tips on researching your ancestors in the U.S. census

1. Decipher codes and abbreviations

Censuses used a lot of codes and abbreviations to make filling out the questionnaire faster and fit maximum information in the small space allotted for each answer. Steve Morse has an excellent guide to deciphering codes in the censuses from 1910 to 1950 on his website: https://stevemorse.org/census/codes.html

2. Verify the identities of the people on the census

Once you find a person on the census, make sure you have identified the correct person and the other people in the household — probably relatives, but occasionally friends, neighbors, or others. Keep in mind that there may be errors and inaccuracies, as we’ll expand upon below.

3. Look around the neighborhood

Flip through the few pages preceding and following the record to find potential parents, married children, cousins, aunts, uncles, and even more relatives, as extended families often lived close together.

4. Begin with the most recent census and work backwards

Build a timeline for each ancestor as you find them in the records. Detail movement as migration occurred and look for changes in marital status, occupation, or address. You can track your ancestors’ wealth and education levels as well as their employment history.

5. Look out for errors

You must keep in mind that the census data is not always correct. You should always expect spelling errors on the census. This happened for any number of reasons: perhaps the enumerator spelled the name phonetically or heard it incorrectly, or the person who provided the information did not understand the questions. Also, it was not always the head of household providing the information — sometimes it was just a neighbor or family member who may not have known the correct answers to all the questions. The handwriting of enumerators was not always easily legible, and transcribers sometimes made errors when transcribing the written data.

The bottom line is, it was a human who gave the answers — sometimes with a foreign accent; it was a human who recorded — and didn’t necessarily understand — the answers; and it was humans who indexed and transcribed the answers, even if they didn’t always correctly decipher the handwriting.

How to look up census records on MyHeritage

MyHeritage has millions of census records from all over the world in its database, thanks to important partnerships with genealogical societies, archives, libraries, and various repositories. This gives MyHeritage and its search engine a huge advantage when it comes to finding family and ancestors.

Because MyHeritage is international, it has content relevant to all countries. Moreover, you can use the search engine interface in 42 different languages. No other genealogy search engine supports so many languages, and our goal is not only to make it useful in your language, but also to add global content that will be useful for your family history research — and to make it accessible to you even if you don’t understand the original language of the record. No matter what language you are searching in, MyHeritage uses intelligent translations to search names in multiple languages, such as Russian, Greek, Hebrew, and Ukrainian, to make sure you never miss a possible record. The translation or transliteration is also applied to the results, so you can understand what names are listed.

Sometimes you may not know the exact name of the person you’re looking for, or that person may have been listed using an alternate spelling or nickname. Don’t worry: when using the MyHeritage search engine, you can control the level of precision to use when searching names. It can match the name exactly, or use the default setting, which will automatically include likely name variations such as Bill and William. Separate matching options are provided for first names and last names in the advanced options. This lets you run exact searches with pinpointed accuracy, or cast a wide net to catch as many plausible variations as possible, and finally find those mysterious ancestors who’ve eluded you so far.

The MyHeritage search engine will even figure out the likely gender of the person you’re looking for. So, if you search for a person called George, the search engine automatically infers that you are searching for a male. Such automatic deduction of gender is among the many unique features not found in other search engines.

Keyword searches are often very useful because they cover many fields, so they can be used to look for a town or a person’s occupation.

MyHeritage is constantly adding new data. This means that even if you don’t find what you’re looking for now, chances are we’ll have it for you very soon.

Can I view census records for free?

You can the search the records for free on MyHeritage, but you’ll need a paid subscription to view the full results.